AI × Governance: Catalysing the Future

What might the CGGI 2024 data tell us about the implications of emerging technologies for governing well?

The introduction in late 2022 of Open AI’s ChatGPT software has promised to bring the 70-year-old dream of artificial intelligence (AI) from the realm of science fiction to reality. The possibilities of this sophisticated app—trained on massive amounts of data and able to quickly generate convincingly human-like textual, visual, and other content from just a written prompt—have inspired fanfare, trepidation, and intense rivalry. And generative apps like ChatGPT are only one form of AI that is transforming how individuals, businesses, and governments manage data, improve task efficiencies, and make decisions.

A 2023 Foreign Affairs article proclaimed AI technology as marking “a Big Bang moment, the beginning of a world-changing technological revolution that will remake politics, economies, and societies”.1 The burning question is: will this revolution be for the greater good, or might it cause serious, even irreparable, harm to society?

While this revolutionary technology will have ramifications across all of society, governments have a leading role to play. They must understand and assess the implications of AI in their own national context, lay infrastructure to unlock its best opportunities, and regulate its use to mitigate significant risks that may arise. Whether AI bodes weal or woe is not a matter of how good the technology is, but how well it is governed.

Benefits of Doing AI Right

Nobel Prize-winning economist Michael Spence, and James Manyika, a Distinguished Fellow at Stanford University’s Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence Institute, have argued that AI could become a leading driver of global prosperity in the next decade, by enabling productivity and growth in a global economy that urgently needs the stimulus.2 While much of this growth will likely be powered by the private sector, successful AI implementation in the public sector could also have a positive effect on the wider economy.3 For instance, one study concludes that in Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates), AI could add value equivalent to some 6% of each economic sector’s GDP.4

For application in the public sector, the use cases for AI are growing all the time and rely on the large amounts of data that governments generate and process. Practical uses range from traffic flow analysis and infrastructure monitoring to public health risk assessments and cyber-attack prevention.

Opportunities to enhance government productivity through AI are significant. It could be particularly effective in improving efficiencies in policy and programme research, design, and delivery—with applications across all functions within government.5 One report estimated that members of the U.S. Department of Social Services had to process, case-by-case, over 70,000 applications and claims each month.6 AI-based automation could dramatically streamline such tasks that consume as much as 70% of workers’ time.7 Early research suggests that AI delivers the largest productivity gains to the least experienced workers.8

Such savings could allow “budget-constrained governments to gradually shift resources from back-office administrative functions to frontline functions interacting with the public,” as Carlos Santiso, Head of Digital, Innovative, and Open Government at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), told Governance Matters last year. AI could also improve outcomes by helping governments identify needs and direct resources in a more targeted and cost-effective manner—such as channelling welfare benefits to the most vulnerable.9

Governments Gearing Up for AI

A report in 2020 found that 50 governments, accounting for roughly 90% of global GDP, had national AI strategies.10 In 2020, nearly half of the United States’ 142 federal agencies had already experimented with AI and related machine learning tools.11 Interest in the governance possibilities of AI is accelerating. In 2023, countries ranging from Rwanda to Tajikistan and from Benin to Senegal all published AI strategies.12 At the beginning of 2024, the OECD tallied more than 1,000 AI policy initiatives stemming from 69 different countries and territories.13

At a global level, the picture is clear: more governments are coming to appreciate the importance of AI. That said, the policies, institutions, strategies, and tools that countries are employing—and the outcomes they are achieving—vary widely. Some are just beginning to outline their AI strategies, while others have been implementing related capabilities for years. Some have advanced digital infrastructures and deep talent pools to build on; others have to start from scratch.

A Strong Relationship Between Good Governance and AI

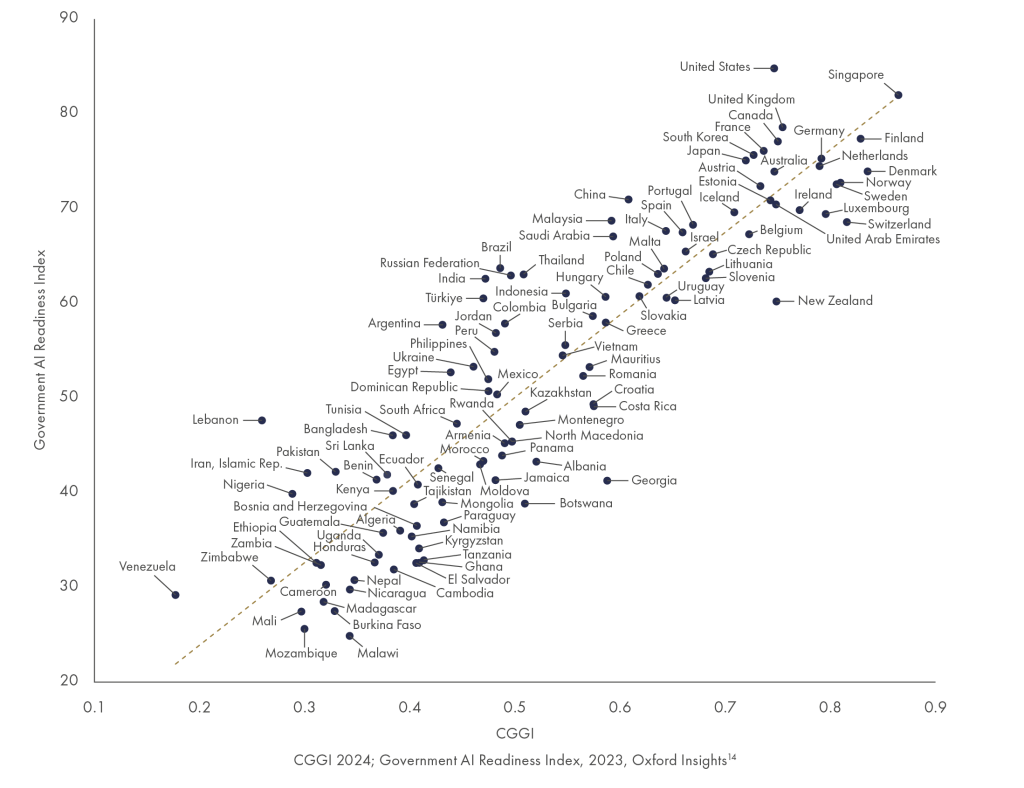

We expect well-governed countries to have made provisions to be more ready to harness the benefits of AI while managing its risks. In turn, we expect better AI readiness to translate into better governance and public outcomes. This virtuous cycle is borne out by a strong correlation between CGGI 2024 data and the Oxford Insights Government AI Readiness Index (see chart below).

Examining the Relationship Between Good Governance and AI Readiness

r = 0.90

The 2023 AI Readiness Index analysed more than 190 governments across 39 indicators (related to government capabilities, the technology sector’s capacity, and data and infrastructure) to address the question: How ready is a given government to implement AI in the delivery of public services to their citizens?

Beyond the overall strong correlation between the two indices, when we examine the relationship between individual CGGI indicators and the Government AI Readiness Index, the four strongest correlations are a mix of government capabilities and outcome indicators, namely Nation Brand, Logistics Competence, Social Mobility, and Data Capability.

The two highest ranking countries for Government AI Readiness are the US and Singapore. Let us look in turn at how each of these countries have calibrated their systems and taken a strategic approach to support AI developments.

UNITED STATES

U.S. predominance in AI worldwide is undisputed.15 It is home to many of the world’s highest-ranked AI research institutions, leading tech companies, and a vibrant AI startup culture. This ecosystem has evolved with the support of government policies that date back many decades.

Today in 2024, the U.S. government actively supports AI initiatives, with various federal agencies investing heavily in research and development. U.S. government investment in AI amounted to $4.38 billion in 2022.16

Initiatives such as the National Artificial Intelligence Research and Development Strategic Plan17 demonstrate the government’s commitment to advancing AI capabilities across all sectors. It redefines the roadmap for the future of AI, for the scientific community, policymakers, educators, and businesses, and emphasises the importance of a shared vision and collective effort to harness the full potential of AI.18 The Plan sets out nine strategies that aim to advance these goals:

- Make long-term investments in fundamental and responsible AI research

- Develop effective methods of human-AI collaboration

- Understand and address the ethical, legal, and societal implications of AI

- Ensure the safety and security of AI systems

- Develop shared public datasets and environments for AI training and testing

- Measure and evaluate AI systems through standards and benchmarks

- Better understand the national AI R&D workforce needs

- Expand public-private partnerships to accelerate AI advances and

- Establish a principled and coordinated approach to international collaboration in AI research.

The US ranks 15th in the CGGI overall, but many of its highest-ranking indicators point to qualities and conditions that support an Attractive Marketplace for AI investments. These include ranking 4th for Adaptability, 7th for Data Capability, and 7th in Stable Business Regulations.

SINGAPORE

The highest ranked country overall on this year’s CGGI, Singapore shows how many capabilities of good governance can come together to enhance a country’s ability to capitalise on the opportunities presented by AI.

Singapore published an AI strategy in 2019, updating it in 2023 in the wake of technological breakthroughs such as ChatGPT.19 Its comprehensive AI strategy is not a standalone effort, but is part of a coordinated, integrated plan—the Smart Nation initiative—to build a “digital government,” “digital economy,” and “digital society”.20

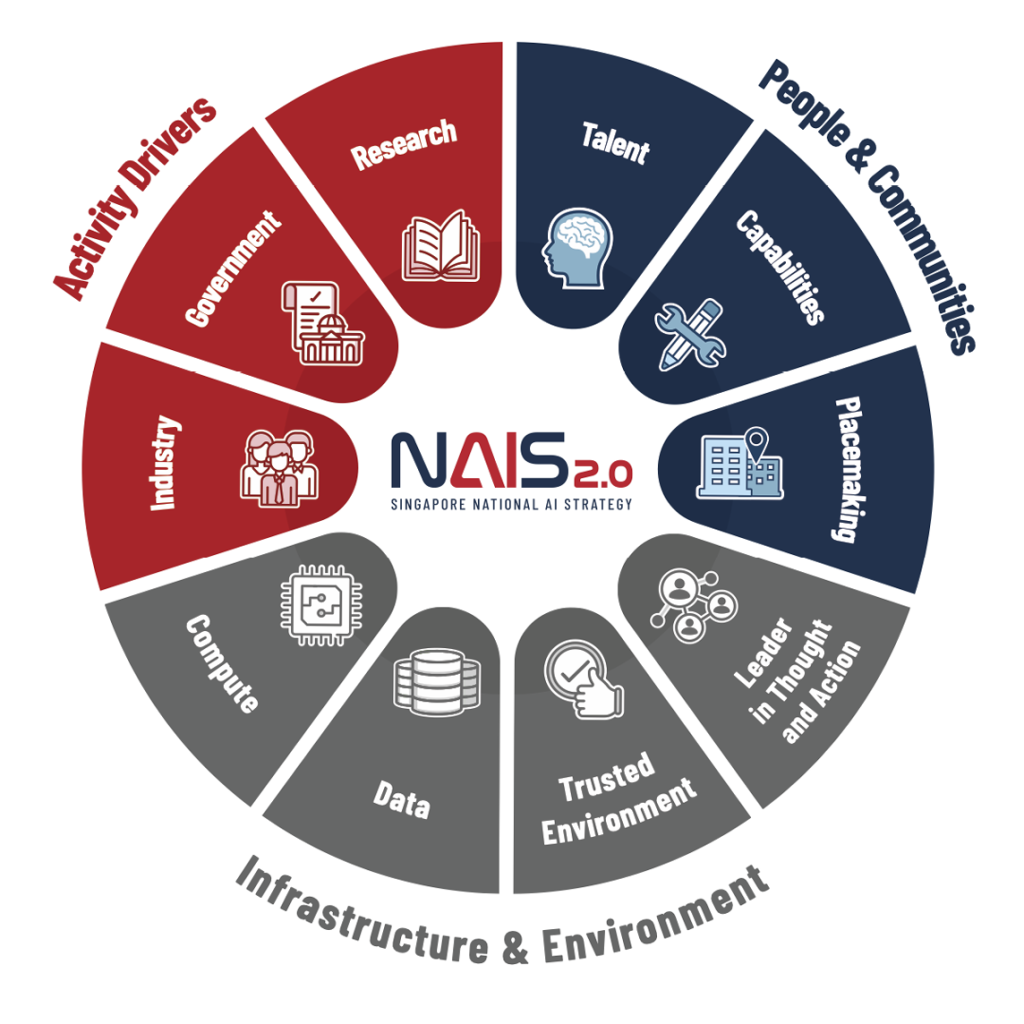

Singapore’s strategy involves developing an “AI ecosystem”, through ten key enablers. These entail not only technical infrastructure but also a skilled workforce to make the most of the technology’s potential, as well as a trusted environment that safeguards users and fosters innovation.

The 10 Enablers of Singapore’s National AI Strategy 2.0.21

Singapore has taken steps to bring these enablers to life with the following approaches:

- Providing AI grants to fund promising AI research and development;

- Collaborating with universities—including the Centre of Excellence for Testing & Research of Autonomous Vehicles (CETRAN) at Nanyang Technological University;

- Launching “LearnAI”, which provides customised training courses for students, educators, professionals, and the public;

- Partnering with the private sector to explore AI prototypes and applications;

- Establishing a Data Science and Artificial Intelligence Division (DSAID), which helps test, implement, and accelerate the technology across a range of government departments and agencies.22

Singapore tops CGGI rankings for governance capabilities that support an effective AI strategy, including Long-Term Vision, Regulatory Governance, and Implementation indicators.

Regulating AI: A Delicate Balancing Act

While AI holds transformative potential for improving government processes and achieving public outcomes, it also poses unprecedented challenges for governance: not least because of the speed at which the technology is advancing.23 Ian Bremmer, President and Founder of Eurasia Group, and Mustafa Suleyman, a co-founder of the pioneering AI-company DeepMind and recently appointed head of Microsoft’s new AI division, argue that what AI demands of governments is “a regulatory balancing act more delicate—and more high stakes—than any policymakers have attempted.”24

Robust Laws & Policies and Strong Institutions will be fundamental to a country’s ability to effectively design and implement legislation that encourages AI’s benefits while managing its risks. Governments need to balance regulation that protects its citizens but also encourage Attractive Marketplace policies that support technological innovation and local industry actors.

According to a World Economic Forum survey of almost 1,500 leaders, the challenge of AI-generated misinformation and disinformation was seen as a more pressing risk in 2024 than armed conflict, an economic downturn, or disrupted food supply chains.25 Even discounting deepfakes and bad actors, AI could still perpetuate, or even magnify, inherent prejudices and inequalities. Concerned observers have noted that bias inherent in the data AI is trained on, which is often discriminatory or unrepresentative of minority or marginalised groups, can lead the technology to produce skewed outcomes.26

Globally, such concerns have led to a number of national and international initiatives to address how AI could be better regulated. The EU’s AI Act, endorsed in March 2024, has been dubbed “the world’s first comprehensive legal framework” on AI. In May 2023, G7 countries began the “Hiroshima AI Process’’ to harmonise their approach to AI governance. The Process includes a set of international guiding principles and a voluntary code of conduct for AI developers. Later the same year, more than 20 Latin American and Caribbean governments signed the Santiago Declaration to Promote Ethical Artificial Intelligence.27 Among other outcomes, the nations agreed to form a working group to create an International Council on AI for the region, focused on improving the region’s capabilities and encouraging collaboration.

There continues to be great disparity in government preparedness for AI, and in how different countries approach its attendant opportunities and risks. Such gaps are set to widen further and faster, as this versatile and fast-evolving technology gives ambitious governments a chance to leapfrog their peers in the governance competition. We will continue to monitor the capabilities associated with sound performance in harnessing AI to improve governance and achieve national outcomes.

Endnotes

- Bremmer, I., & Suleyman, M. (2023, August 16). The AI Power Paradox. Foreign Affairs. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/world/artificial-intelligence-power-paradox

- Manyika, J., & Spence, M. (2023, October 24). The Coming AI Economic Revolution. Foreign Affairs. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/world/coming-ai-economic-revolution

- Berglind, N., Fadia, A. & Isherwood, T. (2022, July 25). The potential value of AI—and how governments could look to capture it. McKinsey & Company; McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-sector/our-insights/the-potential-value-of-ai-and-how-governments-could-look-to-capture-it

- Ibid.

- Carrasco, M., Habib, C., Felden, F., Sargeant, R., Mills, S., Shenton, S., Ingram, J., & Dando, G. (2023, November 30). Generative AI for the Public Sector: From Opportunities to Value. BCG Global; BCG Global. https://www.bcg.com/publications/2023/unlocking-genai-opportunities-in-the-government#:~:text=Generative%20artificial%20intelligence%20(GenAI)%20can,or%20provincial%2C%20and%20local%20governments

- Deloitte AI Institute. (2022). The Government & Public Services AI Dossier. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/us/Documents/deloitte-analytics/us-ai-institute-government-and-public-dossier.pdf

- Chui, M., Hazan, E., Roberts, R., Singla, A., Smaje, K., Sukharevsky, A., Yee, L., & Zemmel, R. (2023, June 13). The economic potential of generative AI: The next productivity frontier. McKinsey & Company; McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/mckinsey-digital/our-insights/the-economic-potential-ofgenerative-ai-the-next-productivity-frontier#key-insights

- Ibid.

- Chandler Institute of Governance. (2021). Public Governance in the Age of Artificial Intelligence. Chandlerinstitute.org. https://www.chandlerinstitute.org/governancematters/public-governance-in-the-age-of-artificial-intelligence

- Holon IQ Education Intelligence Unit. (2020). 50 National AI Strategies—The 2020 AI Strategy Landscape. Holoniq. com. https://www.holoniq.com/notes/50-national-ai-strategies-the-2020-ai-strategy-landscape

- Electronic Privacy Information Center. (2020). Government Use of AI. https://epic.org/issues/ai/government-use-of-ai/

- Oxford Insights. (2023). Government AI Readiness Index 2023. Oxford Insights. https://oxfordinsights.com/ai-readiness/ai-readiness-index/

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (n.d.). OECD’s live repository of AI policies & strategies. https://oecd.ai/en/dashboards/overview

- Oxford Insights. (2023). Government AI Readiness Index 2023. Oxford Insights. https://oxfordinsights.com/ai-readiness/ai-readiness-index/

- Stanford University. (n.d.). Global AI Vibrancy Tool: Who’s Leading the Global Race? Stanford.edu. https://aiindex.stanford.edu/vibrancy/

- Stanford University . (2023). Artificial Intelligence Index Report 2023: Introduction to the AI Index Report 2023.Institute for Human-Centred AI . https://aiindex.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/HAI_AI-Index-Report_2023.pdf

- National Science and Technology Council. Select Committee on Artificial Intelligence. (2023). The National Artificial Intelligence Research and Development Strategic Plan Update 2023

- https://www.dlapiper.com/en/insights/publications/aioutlook/2023/the-us-national-ai-rd-strategic-plan-2023

- Bremmer, I., & Suleyman, M, (2023, August 16).The AI Power Paradox. Foreign Affairs. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/world/artificialintelligence-power-paradox

- Smart Nation Singapore. (2023). National AI Strategy: AI For the Public Good, For Singapore and the World.

- Singapore Government. (n.d.). Smart Nation Singapore. https://www.smartnation.gov.sg/

- Singapore Government. (n.d.). National AI Strategy. https://www.smartnation.gov.sg/nais/

- GovTech Singapore. (n.d.). Data Science and Artificial Intelligence. https://www.tech.gov.sg/capabilitycentre-dsaid

- Chandler Institute of Governance . (2023). Public Governance in the Age of Artificial Intelligence. https://www.chandlerinstitute.org/governancematters/publicgovernance-in-the-age-of-artificial-intelligence

- Bremmer, I., & Suleyman, M.. (2023, August 16).The AI Power Paradox. Foreign Affairs. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/world/artificial-intelligence-power-paradox

- World Economic Forum. (2024). The Global Risks Report 2024. https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_The_Global_Risks_Report_2024.pdf

- Sforzolini, F. S. (2023, December 21). An AI Conversation Unlike Any Other. Brunswick Review. https://review.brunswickgroup.com/article/artificial-intelligence-healthcare/

More Stories

Global Influence & Reputation Country Snapshot: Türkiye