Country Spotlight 2025 & Practitioner Story: Jamaica

Jamaica’s CGGI score has remained stable between 2021 and 2025, with notable rank improvements across several pillars. During this period, the country saw its rank rise in the Strong Institutions (+1), Financial Stewardship (+3), and Global Influence & Reputation (+10) pillars.

In Financial Stewardship, Jamaica has demonstrated notable performance, particularly for the Government Debt and Country Budget Surplus indicators. Over the past decade (2014–2024), the nation has reduced its public debt from 144% of GDP to 72%.1

Also noteworthy is Jamaica’s progress in the Nation Brand indicator, which contributed to the country’s improvement in Global Influence & Reputation. The country welcomed a record-breaking 4.3 million visitors and generated US$ 4.3 billion in tourism earnings in 2024.2 Realising its ambitious 5x5x5 growth strategy, introduced in 2020, Jamaica is on track to welcome five million visitors and generate US$ 5 billion in annual tourism revenue by the end of 2025.3

Jamaica’s CGGI Rank

Jamaica’s Pillar Dashboard

Endnotes

- Eberly, J. C., Eichengreen, B., Henry, P. B., Milesi-Ferretti, G. M. & Steinsson, J. (11 April 2024). How did Jamaica halve its debt in 10 years? Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/how-did-jamaica-halve-its-debt-in-10-years/

- Shillinglaw, J. (27 January 2025). How Jamaica Hit Record Tourism Numbers in 2024. Insider Travel Report. https://www.insidertravelreport.com/how-jamaica-hit-record-tourism-numbers-in-2024

- Davis, G. (5 November 2019). Tourism Sector On Track To Exceed Growth Targets. Jamaica Information Service. https://jis.gov.jm/tourism-sector-on-track-to-exceed-growth-targets/

Activating the Public: Realising Fiscal Reforms in Jamaica

CARICAD Executive Director Devon Rowe, a former Permanent Secretary for Finance, recounts the broad sectoral consensus and concerted leadership behind Jamaica’s remarkable financial turnaround—and what lessons it could hold for other countries in the region.

You have had a long and distinguished career in the Jamaican public service, including as Permanent Secretary in two ministries, among other leadership positions. In your experience, what makes for good governance?

I spent 37 years working in the Jamaican public service, starting out as a temporary clerk right after high school, eventually working my way up to the top level. Growing up in East Kingston in the 1970s, I believe I had an understanding of what the average citizen needs from the government. Back then, we were raised with a sense of mission: to contribute to society. Jamaica’s small economy meant that the government played a crucial role in providing policies and services to benefit a wide range of people, rather than being driven solely by the private sector. These perspectives have always guided my work in government.

One reason Jamaica has stayed relatively stable over the years is that political transitions have always been smooth. Political parties typically work within the law and usually have the full support of a dedicated public service. A huge milestone in the early 2000s was the creation of the Vision 2030 plan, which aims to guide Jamaica towards becoming a developed nation and by 2030 being “the place of choice to live, raise families and do business”.1 Since the plan was developed in a bipartisan way, it continued to be implemented when a new government took over.

In our system of government, the Prime Minister and the Finance Minister are key positions for the achievement of the development agenda or simply getting things done. For that matter, in some Caribbean states, these two roles are sometimes held by the Prime Minister. At the same time, it is crucial for political leaders to have the respect and support of the public sector to ensure alignment between the political and administrative arms of government.

During my time as Financial Secretary in the Ministry of Finance, I made sure that whatever my minister committed to the public was delivered. If something could not be delivered, the ministry worked diligently to put the minister in a position to explain the reasons for deviations and put forward alternatives. This was typical of the ministry and helped support credibility and secure greater acceptance. The public service knows very well that public trust is a vital part of good governance in Jamaica.

Many years ago, the Jamaican government developed a Consultation Code2 designed to guide public consultations for the creation of policy. Though useful, there are not as many consultations as there should be, partly because they can be very costly. Additionally, I think the public should be more engaged in policy discussions. The citizens may not always demonstrate interest in formal settings unless there is a well‑defined or immediate impact. During my time in public service, I also observed a tendency to address matters only when they become urgent, which is not the best approach to governance. Fortunately, over recent decades this challenge has been addressed through medium and long‑term planning.

In government, we do need to step back and think creatively about what we need to do to actively encourage public participation. This is a crucial aspect of governance and was particularly important when Jamaica underwent the IMF‑supported economic reforms programme that began in 2013. As the Permanent Secretary playing a lead role in this effort, it was obvious that a great deal was to be accomplished in a short time span.

Jamaica has made notable strides in Financial Stewardship, including reducing its debt‑to‑GDP ratio by almost half, from 144% to 72% over the past decade. How did Jamaica realise the significant reforms needed for this achievement?

The government created a domestic group called the Economic Program Oversight Committee (EPOC), which included members from the private sector, financial sector, unions, and civil society. This group monitored and supported the reforms internally in (Jamaica), independent of any external review body. EPOC, by being the public face of communication on progress delivering an independent perspective, helped to build trust and social consensus showing domestic and international stakeholders that Jamaica was committed to the reforms. Everyone had skin in the game and were therefore invested in the success of the programme.

Because Jamaica’s economic reforms were part of our own national Vision 2030 plans, we were able to negotiate with the IMF, ensuring that the pace of implementation and conditions for support were best suited to our own practical circumstances and context. We certainly were facing a difficult set of objectives. It is important to note that the Economic Reform Programme has been continued by successive administrations since 2013.

For example, consolidating all our fiscal incentives from many pieces of legislation into one omnibus Act within seven months as a condition of IMF support was not an easy task. My previous experience in legislative changes suggested that this was nearly impossible to accomplish. Yet, working with experts from the private and public sectors, we met the target. Collaboration was an immensely useful asset.

The ministry held meetings across industries and civil society to discuss issues and made amendments based on their feedback. We had a standing provision that recognised that we would not always agree but we had to agree to disagree agreeably when necessary. We worked with a respected tax expert from the private sector, and with expert legislative drafting support, prepared the legislation. The political leadership made it clear that economic reforms were the top priority. Staff from various ministries worked together with the Ministry of Finance to ensure the programme’s success.

We had a standing provision that recognised that we would not always agree but we had to agree to disagree agreeably when necessary.

Internally, the political leadership made it clear that the economic reforms were Job Number One. This meant that staff from across ministries were released from the usual hierarchical arrangements to support efforts with the Ministry of Finance, across and despite silos, to ensure the success of the reform. Cohesion and support at the level of the Committee of Permanent Secretaries were also vital in helping to break down traditional institutional barriers.

With progress came confidence in our collective ability to effect the reforms, and in turn, greater buy‑in.

The government communicated extensively about the programme with unions, the financial sector, and civil society, not just through parliamentary speeches but also through conversations within ministries, town hall meetings, and targeted discussions.

This demonstrates the benefits of having an inclusive process that allows people to participate. While they may not get everything they want, overall, the outcome is in their best interest.

Apart from your economic achievements, what else might account for Jamaica’s growing global reputation in recent years?

Our positive working relationship with international institutions such as the UN, World Bank, and the IMF in the past decade has helped to raise Jamaica’s profile. This builds on the legacy of previous Prime Ministers, who many say set a high standard for Jamaica to be globally recognised in foreign affairs. Jamaica and Jamaicans are recognised as well in sports, music, and the arts. We are signatories to many international treaties and are known for our efforts to live up to the spirit and expectations of the agreements. We have maintained good relations with almost all, if not all countries in the world.

Jamaica is also a pioneer in governance, sometimes taking on issues from which others in the region may learn. For example, as part of our IMF‑supported programme, we carried out a debt exchange, restructured our fiscal system, and introduced new laws. These experiences would have benefitted other Caribbean countries as well. Conversely, Jamaica does not hesitate to research and adapt lessons from the region or elsewhere.

Jamaica’s Statistical Office and systems are among the best in the region. For instance, Jamaica is recognised for good data collection and management, which supports evidence-based decision making. I have also been told that our Vision 2030 plan helped inform the development of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which speaks to its soundness and robustness.

Since your retirement in 2016, you have remained engaged in regional public governance as Executive Director of CARICAD. In your view, what are the main challenges the region faces, and what might be done to address them?

The Caribbean remains economically vulnerable. COVID-19 exposed the fragility of the tourism industry in the region. Climate change will increase the environmental risks we face given Jamaica is already exposed to natural hazards such as hurricanes, volcanoes, earthquakes, and droughts. While economic diversification has begun, it must be accelerated. The region handled the pandemic relatively well, particularly given the limited resources we have at our disposal. It highlighted what in‑country capabilities and systems could do. That said, there is an urgent need to accelerate the improvement of our health infrastructure. I suppose that prevention in our case is cheaper than cure, so we may need to do much more with preventative education. I also think that public sector transformation in areas such as education, agriculture, and technology is necessary.

The future is digital. Digital transformation and the advent of artificial intelligence (AI) can sound terrifying when we think about the potential risk of job losses and it may frighten us into inaction. However, it is also an opportunity for governments to increase skills in the digital realm by providing more opportunities for digital skills, literacy, access, and inclusion.

Climate change is an economic and survival reality for the Caribbean. We are putting lives and livelihoods at the centre of our policy choices. Beyond the talk that we have heard, we need to find ways to gather the resources needed for adaptation or mitigation so that polices can be implemented.

Notwithstanding our small size and limited resources, implementation remains a challenge. Public sector organisations must shift the pendulum from solely process and control to an outcome focused culture. Consequently, skills will have to be enhanced and systems modified to facilitate output and outcomes, whilst retaining rules for accountability and transparency. Innovation, initiative, and good judgement must be rewarded in the public sector without the fear of ending careers for officials making mistakes while seeking to resolve problems. Regionally, we are likely to need better whistleblower protection and better access to information so that we can build trust on which progress will depend.

Finally, exceptional leadership is crucial to raise awareness of the challenges, ensure transparency, dispel distrust, and deliver solutions that support the achievement of the vision. Whether citizens are in the formal workforce or not, young or old, we need to make the most of their capabilities. This mindset change, I believe, will empower our citizens to be activated, enabling our region to deliver and to thrive, well beyond expectations.

Endnotes

- Vision 2030 Jamaica – National Development Plan. (n.d.) https://www.vision2030.gov.jm/

- Office of the Cabinet. (n.d.). Consultation Code of Practice for the Public Sector. https://cabinet.gov.jm/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Consultation-Code-for-Public-Sector.pdf

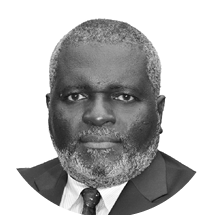

DEVON ROWE

Executive Director of the Caribbean Centre for Development Administration (CARICAD)

Devon Rowe is Executive Director of the Caribbean Centre for Development Administration (CARICAD). He joined the regional organisation in 2016, following a career in the Jamaican public service, where he served as Permanent Secretary in two ministries, and as a Board member of public sector companies in investment, development finance, infrastructure, and health. He is also a member of the Committee of Experts in Public Administration (CEPA) at the United Nations. In 2014, he was conferred the Order of Distinction, Commander Rank by the Government of Jamaica, in recognition of his outstanding contribution to public service.

More Stories

Global Influence & Reputation Country Snapshot: Türkiye