What Does It Take to Meet Public Expectations?

A deeper look into the implications of a CGGI indicator for which Southeast Asian countries dominate the top 10 rankings.

Hearing from the People: Public Perceptions of Good Governance

Good governments tend to produce better outcomes. Good public outcomes create more opportunities for people and a higher quality of life. These in turn should improve people’s trust in government, helping the administration function more efficiently and be in a stronger position to deliver better outcomes, in a virtuous cycle.

In assessing how governments are Helping People Rise, the CGGI includes a panel of nine equally weighted indicators for outcomes over which governments have considerable influence. One of these is Satisfaction with Public Services. This indicator measures people’s satisfaction with their respective public transportation systems, roads and highways, and education systems, using data from the Gallup World Poll.

Interpreting or comparing data based on perceptions is delicate. A range of factors—from culture to local context—can influence opinions and expectations. Decades of academic research tell us that while citizen-satisfaction surveys are useful and important, their findings need to be interpreted carefully.1 Nevertheless, satisfaction surveys offer an important window into the quality of public outcomes, as rated by the people receiving them.

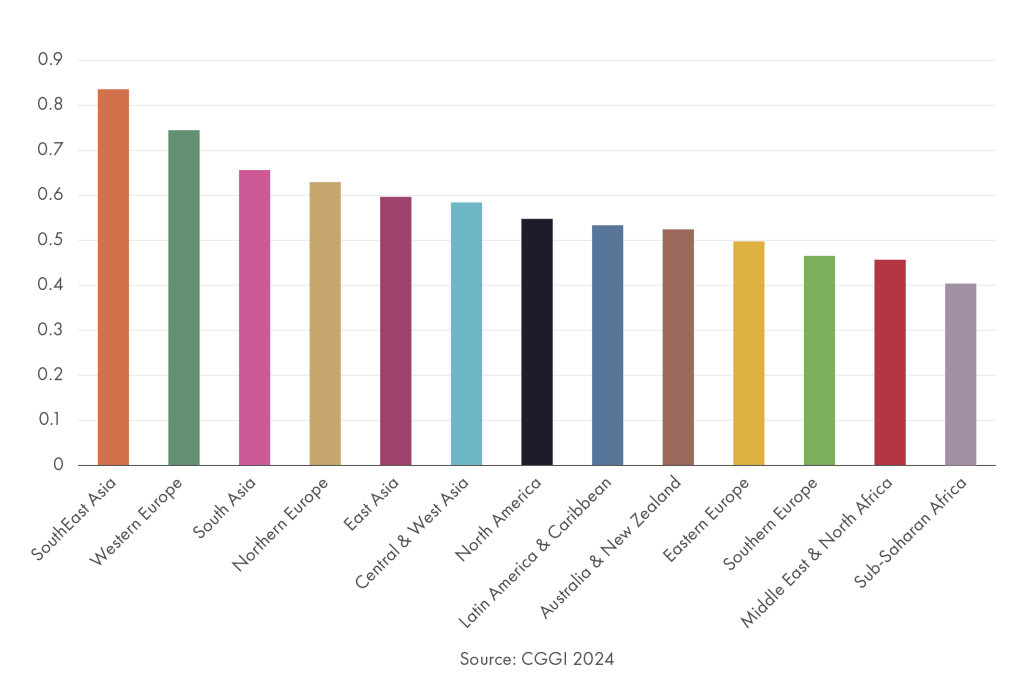

Regional Average Scores for Satisfaction with Public Services

Crucially, such perceptions exist whether public officials are aware of them or not—and whether outside experts agree with them or not. They offer data-driven observations that, paired alongside others, can raise interesting questions about what good governance looks like in practice, and how it is visible in the everyday lives of people.

High Satisfaction in Southeast Asia

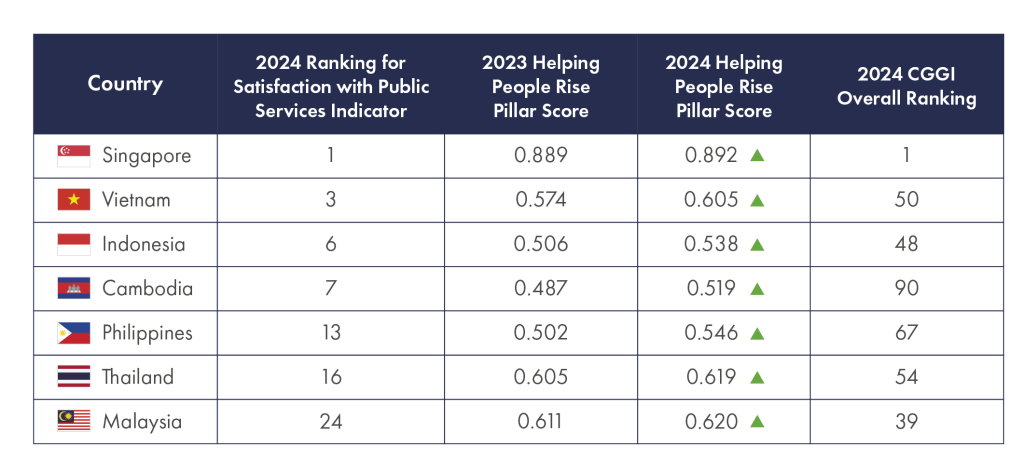

Of the 16 highest-scoring countries in this year’s Satisfaction with Public Services indicator, six are in Southeast Asia—making the region the best-performing worldwide.2 Interestingly, many Southeast Asian countries score high on this indicator relative to their overall ranking in the Helping People Rise pillar—a proxy for the overall quality of a nation’s outcomes—and their overall scores in the CGGI.

One question such strong performance raises is this: Why are citizens in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Indonesia more satisfied with their public services than, say, citizens in Denmark, Finland, or Norway? The three Nordic countries were the highest-scoring countries (in that order) in the Helping People Rise pillar, suggesting that their public services were producing world-leading outcomes—and yet none of the three reached the top 13 rankings in Satisfaction with Public Services.

Momentum Across the Region

The positive momentum in many Southeast Asian countries in the Helping People Rise pillar may help explain why the region excels in Satisfaction with Public Services. Between 2023 and 2024, every country in the region saw their overall score in the pillar improve. For the specific indicators in the Helping People Rise pillar, there was also a broad sense of progress from 2021 to 2024: The region also recorded some of the biggest jumps in this pillar’s rankings: Thailand, Philippines and Malaysia in the Health indicator; Vietnam and Philippines in Income Distribution; Cambodia in Gender Gap; Indonesia in Personal Safety; and Singapore in Social Mobility. In other words, Southeast Asian countries have made strong progress across a number of outcome-related indicators. It is possible this sense of national momentum and progress enhances citizens’ satisfaction with their country’s public services and general governance. Below, we look at three countries from different regions that have made promising gains in improving public satisfaction with government services.

VIETNAM

#3 Overall in Satisfaction with Public Services

Vietnam scored 3rd overall in the Satisfaction with Public Services indicator in this year’s CGGI, ranking 15 spots higher than last year. A number of developments could be contributing to the country’s robust performance in this area.

Vietnam’s sustained economic growth may be a factor. Describing Vietnam as “one of the most dynamic emerging countries in the East Asia region”, the World Bank notes that it has been one of the world’s fastest-growing economies over the past three decades, and one of the best-performing economies throughout the turbulence of the COVID-19 pandemic.3

Vietnam has also made significant investments in transportation and infrastructure—an element that informs the Satisfaction with Public Services indicator. According to one report, Vietnam’s spending on public and private investment in infrastructure in recent years has reached 5.7% of GDP. It has the second highest spending in Asia after China and the highest investment in infrastructure in Southeast Asia.4

Vietnam has made marked progress in other areas tied to a people’s quality of life. The average life expectancy in Vietnam improved by five years between 1990 and 2020; access to electricity and clean water has increased dramatically, and its Human Capital Index is the highest among lower middle-income countries.

The Vietnamese government has also been measuring people’s satisfaction with public services since 2018, through its Satisfaction Index of Public Administrative Services (SIPAS).5 In explaining the rationale for SIPAS, the government stresses the importance of providing all levels of government with objective information about the people’s needs, as well as public expectations for and experiences of services provided by state administrative agencies.

SIPAS findings are used to inform changes that create a culture of people-centred public service, and that encourage the public to take part in governance. According to the Vietnamese Government, in 2022 the national median score of SIPAS was 80%—in other words, eight out of ten Vietnamese surveyed were satisfied.6

In 2021, the 13th National Congress of the Communist Party of Vietnam also called for national governance that is modern and efficient.7 One target set towards this goal is for local and government agencies to have public satisfaction scores of 90% or greater by 2025.8

Digitalisation is one way the country is looking to deliver improved public satisfaction. In 2019, Vietnam launched a National Public Service Portal, where citizens can access more than 2,200 public services online.9 In a country with nearly 80% internet penetration, and where there are more cellular mobile connections than there are people, it is easy to envision how such efforts could help connect people to their government, reduce red tape, streamline administrative procedures, and further increase satisfaction with public services.

KAZAKHSTAN

Climbed 42 Spots in Satisfaction with Public Services since 2021

Since the CGGI was first compiled, no country has climbed more ranks in the Satisfaction with Public Services indicator than Kazakhstan. In 2021 it was ranked 83rd in this indicator; in 2024, it ranks 41st.

Like Vietnam, Kazakhstan has seen sustained economic growth—between 2002 and 2022, its GDP per capita climbed from $1,658 to $11,492.10 This growth, according to the World Bank, has transformed Kazakhstan into an upper middle-income economy that has seen reduced poverty and a rise in living standards. A 2023 survey shows that three in four Kazakhstanis are optimistic about the country’s long-term economic prospects. This economic optimism is also reflected in the greater percentage of people who believe that 2023 was a better time to begin a business than 2022 or 2021.11

Kazakhstan has also been working to digitalise its government—to improve government efficiency and to make public services more accessible. The country’s Digital Kazakhstan programme has set the target of providing 100% of state services online. Among the government’s digitalisation initiatives is the DigitEL (Digital Era Lifestyle) project, which seeks to provide effective public administration that solves the needs of citizens through digital transformation.12 The project features service improvement elements such as a target to deliver faster government services in less than five minutes, tools to enhance social welfare, and platforms to help the government listen to the people more effectively.

Development Asia, an initiative of the Asian Development Bank, has recognised Kazakhstan for its e-government initiatives that make public services more sustainable, inclusive, and equitable.13 This progress seems steady and sustained. An e-government index by the UN ranked the country 83rd in 2003.14 In 2022, the same index ranked Kazakhstan 28th—the 7th highest in Asia.15

Like Vietnam, Kazakhstan not only performed well during the pandemic—public satisfaction with public service delivery in fact increased between 2019 and 202016—but has also been making substantial investments in its transportation infrastructure.

Kazakhstan has drawn attention as a growing transport and logistics centre in Central Asia.17 In 2022, the country invested US$1.2 billion to improve the connectivity and quality of road transport across the country—which included repairing more than 11,000 kilometres of roads.

SENEGAL

Climbed 32 Spots in Satisfaction with Public Services since 2021

Between 2021 and 2024, Senegal climbed 32 spots—the 2nd largest climb for the indicator—to rank 66th for Satisfaction with Public Services.

The IMF calls Senegal ”one of the strongest-growing economies in sub-Saharan Africa”,18 while the World Bank highlights it as ”one of Africa’s most stable countries”.19 Like Vietnam, Senegal’s response to COVID-19 has also been widely applauded.20

Across a number of other indicators—access to electricity, GDP per capita, life expectancy, literacy rates—the country has progressed positively since the start of the 21st century.21

A study by the Global Infrastructure Hub shows that although Senegal’s infrastructure quality lags behind its peers, it invests a greater percentage of its GDP (10%) in infrastructure than countries at a similar income level. Senegal focuses actively on attracting investment for infrastructure projects.22

Senegal’s government is also enacting a national strategy, known as Sénégal Numérique 2025 (SN2025), to transform Senegal into a digital society, with improved public service delivery among its goals. Senegal’s strategy has been noted for its participatory approach, which encourages buy-in and implementation among stakeholders.23 Such an approach could meaningfully improve public satisfaction in two ways: by making public services more efficient, effective, and responsible to public needs, and by fostering a broader sense of participation and inclusion.

What Lessons Might Other Countries Learn?

Satisfaction can be subjective, and there are many factors that inform public perception of government services. But apart from having performed well in Satisfaction with Public Services, the countries discussed above also show several traits in common: they feature strong economic growth and the opportunities that flow from it, they make significant investments in infrastructure, and they pursue digitalisation efforts to streamline government services and broaden access. Digitalisation in particular could help countries leapfrog decades of inadequate infrastructure, leading to step improvements in meeting expectations of service delivery, which may then attract greater public satisfaction.

A country’s overall CGGI score tends to remain relatively stable year on year: the core capabilities of governance take years, if not decades, to build. Nevertheless, we do see more marked improvements in individual indicators. As Vietnam, Kazakhstan, and Senegal attest, stronger gains in public satisfaction are possible, even in challenging times and circumstances. One lesson seems clear: progress is possible.

Endnotes

- Favero, N., & Kim, M. (2020). Everything is Relative: How Citizens Form and Use Expectations in Evaluating Services. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 31(3). https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muaa048

- The regional classifications used in this commentary are based on the United Nation’s M49 standard (https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/) and World Bank (https://data.worldbank.org/country)

- World Bank. (2023). Vietnam Country Page. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/vietnam

- Source of Asia. (2023, April 19). Driving Change: Vietnam’s Ambitious Plan for Transportation Infrastructure Improvement. https://www.sourceofasia.com/vietnam-ambitious-plan-for-transportation-infrastructureimprovement/#:~:text=Vietnam%20will%20construct%20tens%20of,Singapore%2C%20Taiwan%20and%-20South%20Korea

- Nguyen, B. C., & Nguyen, N. T. (2022). The Impact of Good Governance on the People’s Satisfaction With Public Administrative Services in Vietnam. Administrative Sciences, 12(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12010035

- Nam Dinh newspaper. (2023, August 7). To increase people’s satisfaction with state administrative agencies— Vietnam.vn. https://www.vietnam.vn/en/de-tang-su-hailong- cua-nguoi-dan-voi-co-quan-hanh-chinh-nha-nuoc/

- Communist Party of Vietnam. (2021). Document of the 13th National Congress of Deputies. Hanoi: National Truth Publishing House. https://en.nhandan.vn/documents-of-13th-national-party-congress-in-five-foreign-languagespost110289.html

- Mai, N. (2022, September 15). Vietnam targets satisfaction with public services at 90% by 2025. Hanoi Times. https://hanoitimes.vn/vietnam-targets-publicsatisfaction-for-administrative-performance-at-90-by-2025-321795.html

- Ministry of Industry and Trade of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (2019, December 10). National public service portal launched.

- Kemp, S. (2023, February 13). Digital 2023: Vietnam. DataReportal. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2023-vietnam

- World Bank Group. (2024, February 19). Average Life Satisfaction Around 70 Percent in Kazakhstan, Shows World Bank Survey. World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2024/02/01/averagelife-satisfaction-around-70-percent-in-kazakhstanshows-world-bank-survey#:~:text=ASTANA%2C%20February%201%2C%202024%20%E2%80%93,of%20the%20survey%20in%202021

- Nartayev, A. (2022, September 12). How Kazakhstan Is Making Public Services Inclusive and Sustainable. Development Asia. https://development.asia/explainer/how-kazakhstan-making-public-servicesinclusive-and-sustainable

- Ibid.

- United Nations. (2003). Global E-Government Survey 2003. https://publicadministration.un.org/egovkb/enus/Reports/UN-E-Government-Survey-2003

- United Nations. (2022). United Nations E-Government Survey 2022. United Nations.

- United Nations Development Programme. (2021). Public satisfaction with public service delivery increases in Kazakhstan. UNDP. https://www.undp.org/kazakhstan/press-releases/public-satisfaction-public-service-deliveryincreases-kazakhstan

- International Trade Administration. (2020). Kazakhstan Country Commercial Guide. https://www.trade.gov/kazakhstan-country-commercial-guide

- International Monetary Fund. (2023, July 12). Senegal’s Growth Prospects are Strong. IMF. https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2023/07/12/cf-senegals-growthprospects-are-strong

- World Bank. (2024, March 22). Senegal Country Page. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/senegal/overview

- BTI Transformation Index. (2022). Senegal. BTI Project. https://bti-project.org/en/reports/country-dashboard/SEN

- World Bank data.

- Senegal. (n.d.). https://www.gihub.org/countries/senegal/

- Vota, W. (2024, January 24). 10 Examples of Successful African e-Government Digital Services. ICTworks. https://www.ictworks.org/examples-african-egovernment-digital-services/

More Stories

Global Influence & Reputation Country Snapshot: Türkiye