Building a Culture of Integrity to Combat Corruption

The University of Oxford’s Professor Chris Stone has spent his career exploring how government systems can operate with greater integrity. Here, with Chandler Institute of Governance’s Executive Director, Wu Wei Neng, he discusses leadership and culture change, corruption in the age of COVID-19, and why many attempts to instil integrity are short-lived “sugar highs”.

Throughout his career – first as a public defender in Washington, DC, followed by a tenure at Harvard University, and then as President of the Open Society Foundations – Professor Chris Stone has always combined a study of good governance with real-world implementation. He has worked with government reformers across five continents and in 2005 received an honorary OBE for his contributions to criminal justice reform in the UK. Professor Stone currently serves as Professor of Practice of Public Integrity at Oxford University’s Blavatnik School of Government.

Corruption scandals are never far from the news, and we have seen more cases come to light in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. What are these new challenges governments are facing?

Chris Stone (CS): The pandemic has stressed anti-corruption mechanisms at every level. Take frontline corruption, the petty kind perpetrated by individual police officers. During lockdowns in Nigeria and Zimbabwe, for example, we saw allegations that some police officers and border guards were soliciting or accepting bribes to let people travel or ignore COVID restrictions. This kind of corruption not only further undermines trust, but also adds public-health risk. In that sense, the pandemic has enlarged familiar, longstanding patterns of corruption.

As huge amounts of money are spent very, very quickly by governments in response to the pandemic, we are also seeing widespread procurement fraud in local and national governments. To respond with the speed required of the situation, many governments suspended their normal procurement procedures. Sadly, but not surprisingly, we’ve seen allegations of everything from cronyism to outright fraud in South Africa, the UK, the US, and beyond. Part of it, at least, is that officials think, “I need to get this done quickly. I don’t have time to go to the market. I’m going to work with somebody I know”. Sometimes they know of a particular supplier because they provided reliable service in the past; sometimes they know them because they’ve attended parties with them, or they have family members in the company. When you suspend the normal rules, it’s not surprising that we see patterns that look quite corrupt.

And at the highest level, the facilitation of international corruption has also been enlarged. This is interwoven with the procurement fraud and the corrupt distribution of financial support to businesses. The scale of some of these transactions, loans and subsidies in the hundreds of millions of dollars, requires the participation of international financial networks: accountants, bankers, and lawyers. The usual range of facilitators are helping obtain, move, and hide these vast sums. Sometimes this assistance is knowingly corrupt, at other times wilfully blind to the corruption, but certainly culpable.

In short, whenever governments decide to spend huge sums urgently, the opportunities for corruption expand and our cultures of integrity are tested. The global pandemic has seen governments worldwide spending big and fast, testing integrity like never before. We’ve seen some terrific government responses: with countless public servants putting the public interest first, selflessly and often at great risk to themselves. But alongside this, we’re also seen a predictable enlargement of corruption.

All of this can erode public trust at a time when governments need it most to manage a public health crisis. How can government leaders, to use the slogan, ‘build back better’?

CS: There is no question in my mind that governments can win back public trust. Even the most cynical members of the public are willing to invest their confidence if they see real effort. However, we don’t often find evidence that governments are harnessing that confidence to build and secure trust for the longer-term.

More often, it’s like a “sugar high”. After a scandal, some governments act swiftly to restore trust and get this short-term boost. The public gets excited. There’s a sense of movement but then the question is, can the government actually sustain it? Has the government changed the culture and blocked the systemic opportunities for corruption, or was this just a show? Is there the political will to continue for the long haul? Is there real change?

That’s where South Africa is poised right now. Will the anti-corruption efforts be sustained? We don’t know. Similarly in Europe, in Italy for example, it will also be very interesting to see what happens over the next few years. The nationwide mani pulite (‘clean hands’) investigation of the early 1990s uncovered staggering levels of corruption in the country. There were prosecutions in the wake of the investigations and these produced a kind of sugar high—people went to prison, political parties collapsed because of the scandals, and there was hope that things were going to change. And then, because efforts never extended beyond the courts, the election of Silvio Berlusconi ushered in a new decade of cynicism and resignation about the state of corruption.

How will Italy, South Africa, and other countries fare in the wake of COVID? Will they use the opportunity to build public confidence in government integrity and sustain it in the long run? They definitely have a chance. Will they seize it?

The default response to ‘fix’ corruption is often to prosecute offenders, beef up anti-corruption agencies or anti-corruption laws. Does this work?

CS: Criminal penalties don’t usually address patterns; they typically confine the scandal to a few people. But every once in a while, criminal prosecutions can be used to change the pattern, not just punish an individual. It’s rare, but it happens. When Eliot Spitzer was the Attorney General of New York in the early 2000s, he famously prosecuted a hedge fund for illegal late trading, changing a widespread practice almost overnight. The prosecution threw a spotlight on trading practices that had become corrupted, and while the legal results were just a few guilty pleas and fines, one strategically deployed indictment changed the pattern of financial misconduct across an industry. Whether you’re at the International Criminal Court, or you’re a small town prosecutor, your dream is to bring a small number of cases that lever the bigger change you want. But it’s very hard and very rare. Almost always the bigger change has to come from changes in governance, management, personnel practices, using the other tools we have. It’s so easy to say, but hard to do: you want to change the culture, not just punish the individuals.

So how do you go about changing culture?

CS: If you look at a company that’s lost public confidence for whatever reason – a bad product, mistreatment of employees, for example – a good, new CEO will always set out to change the culture. He or she won’t rely simply on setting up a monitoring agency or reiterating existing policies; they will launch a broad programme to change the culture.

Culture change is achieved through countless messages, rituals, and other touchstones inside an organisation. Criminal law and anti-corruption agencies are crucial in maintaining pressure to strengthen a culture of integrity, but external monitoring and external punishment can never change internal culture on their own.

Leadership has to turn that culture around. It has to focus on accountability for past corruption that everyone knew about but went unpunished, while also making sure that anybody who is corrupt in the present risks being caught. There has to be monitoring, surveillance, and protection for whistleblowers. And there has to be investment in the organisation’s long-term culture: who you’re hiring, who you’re promoting, and how you are hiring and promoting them: the integrity rituals you’re building into the organisation.

Can you share a little more about those rituals?

CS: They could be something as simple as how people are celebrated when they retire. The people who are beloved and have high integrity always say, “I don’t want you to make a big fuss over me. I don’t want a big party”. But there’s another reason for the party – it’s is a place to tell stories that entrench culture. Those kinds of rituals are incredibly powerful in any public or private organisation. They’ve got nothing to do with the criminal law, nothing to do with an anti-corruption agency. They’re about leadership. Rituals alone aren’t the answer for corruption, of course. You need external oversight, investigations, and criminal law. But the hard work and the real turnaround happens inside the organisation.

There is no question in my mind that governments can win back public trust. Even the most cynical members of the public are willing to invest their confidence if they see real effort.

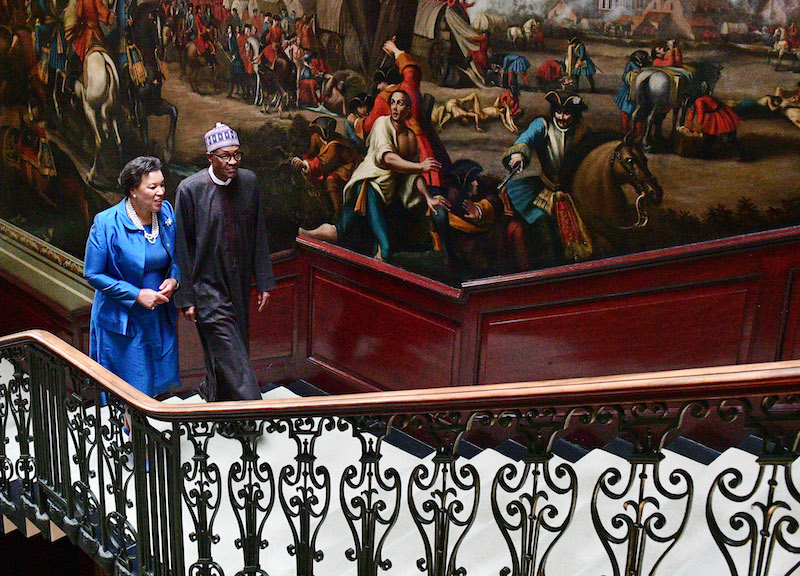

Professor Chris Stone, Professor of Practice of Public Integrity at Oxford University’s Blavatnik School of Government

Are there any countries that have done this well??

CS: The turnaround examples I know best in the public sector are related to police corruption. This is a global problem, which makes it ideal to study, for example comparing best practices in what we criminalise, what we monitor, and how we conduct integrity testing. So much police work is done out of public view. This is an area where substantial money, technology, and effort is invested to stem corruption, and yet there’s still significant police corruption worldwide.

What inevitably matters is individual leadership. Leaders really make a difference, often in partnership with their oversight agency. That’s true whether you’re talking about the police in Nigeria or Los Angeles.

Years ago, I worked alongside some excellent leaders in the Nigerian state of Lagos, including both an Attorney General and a district police chief who was willing to arrest and punish corrupt officers. The public noticed their commitment. You could see that determined leadership, even in a highly corrupt environment, could build integrity in a particular command. Similarly, in Los Angeles, when Bill Bratton became Police Chief and André Birotte became the Inspector General of Police as the outside monitor, the two built a partnership that made a significant difference to the culture of the department. It was acknowledged even by community organisations and legal watchdogs like the American Civil Liberties Union.

I find examples of effective police reform all over the world—in a handful of U.S. cities, as well as in Chile, in Brazil, in India—and it’s invariably tied to leaders. The problem is institutionalizing the cultures of integrity, because those leaders change and corruption slips back in.

So you wind up in this curious situation. On the one hand, we know how to change corrupt cultures. It’s not just about resources. In countries at every income level, leaders can improve the integrity of their departments. And yet, it can be hard to find examples where the change has lasted through multiple changes in leadership. It really is first about leadership, then reinforcing structures and sustaining that change to build a lasting culture of integrity.

More Stories

Governance Competition: The Winners in 2025