The Tradecraft of Capability Development

Wu Wei Neng

Executive Director, Chandler Institute of Governance

If capabilities matter, and countries differ widely in their government capabilities, then how can governments take active steps to improve their capabilities over time? Given the diversity of national circumstances and needs, there is no fixed formula or pathway to do this. However, there are principles and frameworks that we can learn and adapt from the experiences of successful governments around the world.

Understanding Capabilities

Years ago, I called on a government Minister during an overseas trip. I hoped to learn more about his priorities and the challenges he faced. He welcomed us warmly, and asked me about my impressions of his country. As I spoke, he started to write some notes, but realised that his pen did not work. Slightly embarrassed, he called for his assistant, who brought in another pen. Amazingly, that one didn’t work either. He then realised that his staff had given him the wrong file, which was intended for a different meeting.

While such stories are not uncommon, I have also experienced government effectiveness at its best. In fact, some of the most capable people I’ve ever worked with have been civil servants, who combine dynamism, commitment and intelligence with a strong sense of public duty.

Government capabilities are the range of competencies, skills, platforms and levers that governments need to perform their roles, such as policymaking, regulation, financial management, and the provision of public services. There is nothing mysterious or abstract about the need for strong capabilities in any organisation, whether public or private. Strategic planning and data analytics skills are examples of capabilities, but so is competent operational and staff support for government leaders, so that they are well briefed, and have the equipment to do their job – even down to a humble pen.

The Chandler Institute of Governance is dedicated to supporting and working with governments around the world to strengthen public leadership, policymaking and institutional effectiveness. In the course of our work, we have identified key aspects of capability development that are relevant to all countries, regardless of their income level, political system or cultural context.

Story and Culture

Beyond the daily administration of government, public sector leaders have a responsibility to shape the story and culture of public service. Too often, leaders focus mainly on process improvements or “input” based measures such as increasing staff strength. This ignores the powerful role of narratives and perceptions in enabling good government performance. In some countries, government service and careers in government are seen as inferior options to more exciting and highly paid corporate jobs. This results in a “negative culture spiral”, where talented government officers aspire to leave for the private sector, while people who apply for government jobs seek routine and a stable paycheck. Over time, this culture becomes self-reinforcing.

This is a lost opportunity, because public service speaks to the intrinsic motivations of many. Sharath Jeevan, founder of Intrinsic Labs, notes that government leaders have a fantastic opportunity to appeal to the values and thirst for meaningful work that many younger, talented jobseekers have. Culture cannot be created overnight, but it can be nurtured through the celebration of organisational role models, workplace stories and traditions, identity markers such as uniforms and logos, and opportunities for genuine, frank conversations at all levels.

If government leaders embody positive values and culture in their own conduct and lives, they will be powerful role models for their staff and colleagues, and leave positive legacies long after their tenures in office have ended.

Leadership and Talent

An organisation’s talent system is its lifeblood, particularly in government where a diverse range of skills and competencies are needed across a broad spectrum of job functions and disciplines. Many successful governments have leadership schemes that focus on developing and nurturing future senior public sector leaders from an early stage in their careers. These schemes focus on rigorous meritocratic selection, the exposure to a broad range of government work across Ministries and agencies, and opportunities for mentorship. Subject matter specific schemes such as a legal specialists scheme or a procurement experts scheme also allow governments to offer competitive pay and promotion for specific types of skilled talent they require.

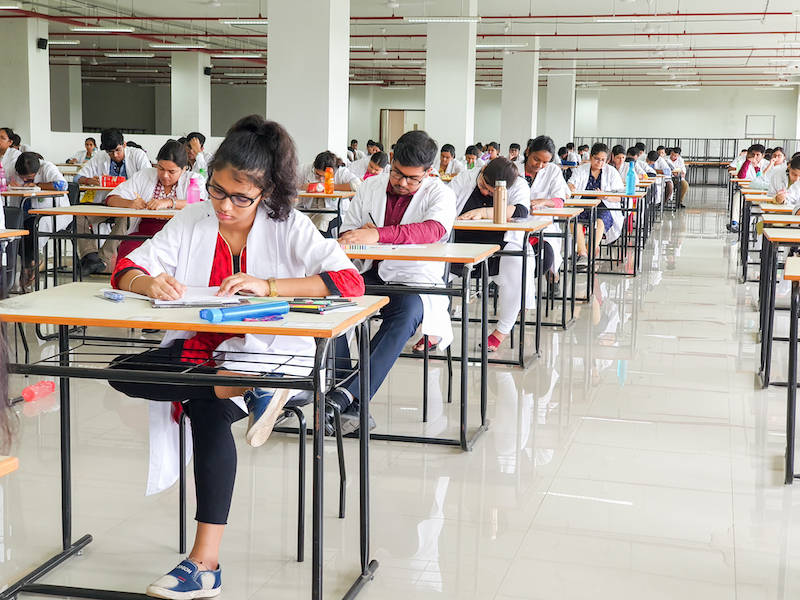

Another feature of successful governments is a commitment to the training and development of staff. National academies of public administration and civil service training institutes are essential for the documenting and sharing of both explicit knowledge and tacit wisdom. Such training institutes must be as practical and pragmatic as possible, focusing largely on the actual skills and techniques required for successful public administration.

Talent systems are built from several key components – attraction and recruitment, development and training, on the job learning, promotion and demotion, performance evaluation and review, workplace incentives (either monetary or non-monetary in nature), disciplinary action and probation, and inter-agency transfers or secondments. Sound talent management systems recognise that these components form an integrated whole that is more than the sum of its parts. This, coupled with a culture of respect for ability and skills, and a commitment to talent development, will help governments attract their fair share of the nation’s talent pool.

Institutions and Processes

Strong institutions and processes ensure that civil service organisations are robust, and can withstand the ever-shifting circumstances of political change. There is a delicate balance to be struck here. Civil servants are tasked to serve the government of the day, its leaders and institutions must therefore be non-ideological, focused on achieving the goals expressed by the political leadership with a public mandate. However, the civil service also needs to defend its role, and protect itself from becoming marginalised or bypassed by political leaders who may at times attempt to undermine state institutions and legal processes. It can best do so by being focused, capable and professional, and earning the respect of politicians and citizens alike.

Strong institutions need to have robust processes and provide continuity as leaders change. To do this, they need clear terms of reference and mandates, as well as established, strategic, command and implementation structures. Professional processes, such as dedicated departments for human resource management, finance and procurement, audit, knowledge management, building management and communications, are needed to effectively support the policy and planning departments.

Even the best designed institutions and processes will need periodic review and adjustment, as new developments in culture, technology, citizen expectations and international norms occur. Annual leadership review platforms are useful for signposting the importance of adaptation and ensuring long-term relevance, amidst the hectic bustle of daily work.

Strategies and Plans

Many government organisations craft strategies and plans that appear very sensible and comprehensive, but are not translated into useful actions and outcomes on the ground. There are at least three reasons for this. First, the government agency may lack the capabilities, manpower and budget to implement the strategies and plans. Second, the strategies may look good on paper, but may not be appropriate for the current needs of the country and its citizens. Third, there has not been sufficient alignment or commitment from important stakeholders to drive the strategies and plans forward.

When done well, strategies and plans are an excellent platform for developing and aligning an organisation’s purpose, priorities and resources, and then communicating these. However, the strategic planning process in many governments may be inadequate for several reasons. Strategies are often aspirational, but not grounded in a firm and unvarnished understanding of an organisation’s strengths and limitations. This often results in unrealistic medium or longer-term visions and commitments that the organisation has no capabilities to eventually deliver. Strategies are also often expressed in the form of goals and timelines, but without a clear pathway to implementation, nor a clear sense of who is accountable for each step. Governments often engage external experts or consultants to draft their strategies for them, which often results in a mismatch of hopes and reality, since it is difficult for even well-meaning external parties to understand the deep context and realities of a government.

Good government is an important foundation of national development and prosperity, and capability development is an ongoing journey for all governments, regardless of their current effectiveness and performance.

Wu Wei Neng, Executive Director, Chandler Institute of Governance

Implementation and Delivery

While governments do not generally operate in the commercial marketplace, they are nonetheless responsible for providing, or ensuring the provision of, a wide range of goods and services. These range from amenities like sports facilities and libraries, to infrastructure like ports and railways, to services like public healthcare, education and security. They need the capabilities to implement and deliver these public goods and services to a very diverse range of citizens, businesses and other stakeholders.

In our experience working with governments around the world, we realise that government leaders and officers often have an abundance of good ideas and plans. What is lacking, by their own admission, is the capacity to take a strategy or plan, break it down into practical workstreams, targets and timelines, assign the necessary people and resources, and perform the micro-actions such as organising public briefings, conducting regulatory inspections, or managing procurements and logistics. These steps convert a good idea into concrete outcomes that people value. Establishing a culture focused on implementation requires that leaders be recognised for solid execution of plans, and not just the writing of strategy memos, and that officers be well trained in areas such as project management, operations and staff work.

Sound implementation also relies on effective monitoring and evaluation of past initiatives and ongoing programmes, so that insights and lessons from these can be used by governments to further improve. Monitoring systems do not have to be costly, and can leverage on readily available, existing administrative data such as student test scores, participation rates and crime data, that is collected during the daily business of government.

Good government is an important foundation of national development and prosperity, and capability development is an ongoing journey for all governments, regardless of their current effectiveness and performance. Undertaking this journey in a pragmatic, thoughtful and intentional manner will greatly improve a country’s chances of success.

More Stories

Governance Competition: The Winners in 2025