Technology, Culture and Trust: A Conversation with Li Hongyi and Chan Chi Ling, Director and Deputy Director of Open Government Products, Singapore

LI HONGYI

Director, Open Government Products, Singapore

CHAN CHI LING

Deputy Director, Open Government Products, Singapore

Good government is about making people’s lives better, but the big question is how. The most important starting point is to honestly and openly understand what the problems are on the ground.

Li Hongyi, Director, Open Government Products, Singapore

Hongyi: What if we took how a modern technology company was run, and applied that to public sector problems? Before joining the government, I worked in Google for about two years. About two years ago, I set up what is now Open Government Products (OGP) because I saw the really powerful ways that technology can deliver services and run organisations better.

Companies like Google apply really sophisticated and intricate systems and technologies to what are frankly quite small questions. There were dozens of PhDs spending months to determine the optimal shade of blue for web links. Meanwhile, governments have good people who work very hard, but their tools are nowhere near as sophisticated – and they’re making important decisions on things like healthcare, transport, housing and care for the elderly. That became my mission – to take some of the technology that companies like Amazon and Facebook use to do things like target ads, and adapt that to improve the way governments can target social assistance or run our operations.

Traditional government IT systems are defined by domain rather than capability. Take, for example, a hospital administration system or a transport coordination system. Each is huge and trying to track and do a hundred different things. Our products each focus on doing one thing only and doing it well. FormSG builds forms – a government agency can put together an online form and start collecting information in 20 minutes. Isomer enables government departments to build and launch a website very quickly.

If you have tools that are simple to understand and can be combined in different ways, you can respond more quickly when needs change. When the pandemic hit, we needed to recruit healthcare volunteers. In less than a week, we used Isomer to build a website, FormSG to design the recruitment forms, and Go.gov.sg to generate QR codes and links. You string these various pieces together and you have a recruitment system. There’s no need to build a big specialised platform.

Our HR systems are also critical. In traditional government structures, political office holders are the brains and set the direction while the civil servants execute what they request. This can be useful for traditional problem solving, but my role as Director of OGP is not to tell people what to do – it is to support the team by creating the environment, culture and processes to help them perform at their fullest potential.

Chi Ling: Prior to joining the experimental outfit that is OGP, I spent some time in a strategy unit and a line ministry in the Singapore public service. In my experience implementing policies and operational plans within government, success in execution depends on the right people – with the right values and skill sets – as well as the right environment and structures. The former often depends on its leadership and the way they recruit and develop people, whereas the latter refers to promotion structures, feedback and appraisal mechanisms, and culture.

The best organisations create a culture of responsibility and accountability, and encourage learning and development. In the case of OGP, we have experimented with using peer appraisals not just for the purpose of providing development feedback, but also for assessment and promotion. We also set aside time for continuous learning, by designating the month of December as ‘Open Learning Month’, and every Friday as a team learning day.

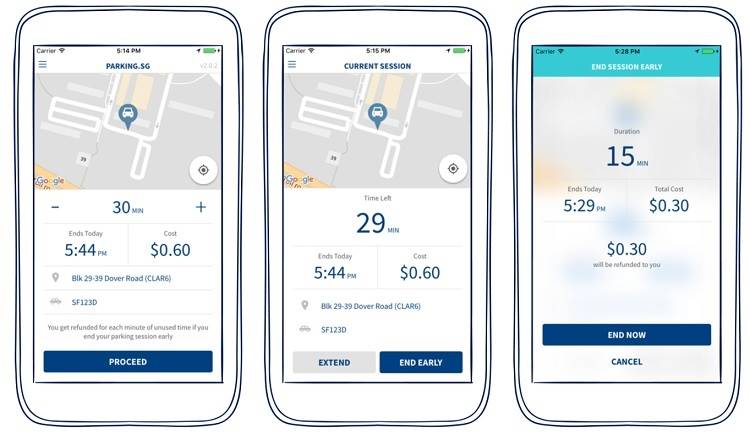

Hongyi: We are responsible “end to end” for getting things done. Our people are not cogs in a machine, each in charge of a narrow function. When we launched Parking.SG, the Product Manager helped debug technical issues and the Engineers responded to support tickets. Teams are small – two to five people. Each has their individual specialisation, but everything is everybody’s job. When you build this culture, everybody gets down to brass tacks.

Chi Ling: We are disciplined at reducing complexity by keeping team sizes small and focusing on a clear product vision. A tempting instinct of many organisations is to throw more people at a problem. There is value in having larger teams under certain circumstances, but this cannot substitute clear focus on the right vision. A product vision is not necessarily what senior leadership wants, nor what users or citizens say they need. It is born out of insight and observation from examining a problem space thoroughly. Often this involves trial-and-error, gathering data and feedback, and being close to the ground.

This was the case for how OGP built systems to support vaccination operations – the end-to-end vaccination operations system was built within weeks by a small team of product managers, designers, and software engineers working closely with policymakers, clinicians, and ground operators. Having a clear product vision helped us to prioritise across requirements and features, guided us to say no to certain stakeholder requests, and ultimately helped us achieve better outcomes.

Hongyi: I intentionally under-resource our teams, because when people are constrained in this way, they become more driven and creative. Look at small business owners in Singapore – each of them handles logistics, procurement, payments, hiring, pricing, safety, taxes, and customers. It is easier for large organisations to languish in inefficiency because responsibility is diffused. But when you have a five-person team and the product is not working, everybody gets down to solve the problem.

Everybody at OGP will tell you that there are a dozen other things we could be doing, but we are not. And that is good, because we are very clear about prioritising and doing the most important things, and shelving less important things. That forces us to be very deliberate.

Good government is about making people’s lives better, but the big question is how. The most important starting point is to honestly and openly understand what the problems are on the ground. Collecting and using basic data goes a long way. There are a whole bunch of contentious value statements we can debate, but there are also universal things we can all agree on – countries should have fewer babies dying, fewer people homeless, more children in school, lower workplace stress levels.

There are debates over questions like whether public or private healthcare systems are better. In most cases, the philosophical differences are less important to whether a system succeeds or fails, compared to the quality of the implementation. It turns out you can make a lot of things work. We don’t carry a torch for any particular doctrine, except doing what is right for people. Good government is ultimately very pragmatic, iterative and convergent. It is about trying things out, figuring out what works, being honest with yourself, and helping people understand what you are trying to do.

Chi Ling: Catering to people’s needs is often touted as the hallmark of good government. Beyond this, good governments must build trust with citizens, to be able to explain why some demands cannot be met, or why a policy didn’t work. This reservoir of trust enables governments to communicate hard truths to citizens, to be heard and understood. It also creates a two-way street that empowers people to speak up and tell the government hard truths it needs to hear.

Good governments must build trust with citizens, to be able to explain why some demands cannot be met, or why a policy didn’t work. This reservoir of trust enables governments to communicate hard truths to citizens, to be heard and understood. It also creates a two-way street that empowers people to speak up and tell the government hard truths it needs to hear.

Chan Chi Ling, Deputy Director, Open Government Products, Singapore

Practitioner Stories are told in the contributor’s own words, speaking in their individual capacity. Their inclusion in the CGGI Website is not an endorsement of the CGGI 2021 methodology or results.

More Stories

Country Spotlight 2025 & Practitioner Story: Jamaica